Bobby and the Big Russell by Bruce Steeples

Bobby and the Big Russell

by Bruce Steeples

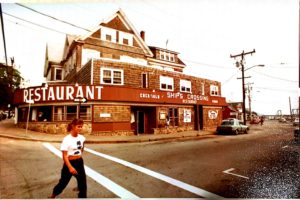

Cape Cod, 1975

The first summer ferry to Martha’s Vineyard left Woods Hole at eight a.m. Across the street, the line started forming outside the Ship’s Crossing Restaurant about a quarter to seven. When the doors opened at seven there was a rush to the tables and soon a stack of orders were hung from the rail above the hot griddle. I was fifteen and pretty proud of myself for making the leap from dishwasher to kitchen in just a couple of weeks, even if it was only to work the toast position during the rush. Sometimes we would serve over a hundred breakfasts before the first boat. Most patrons came from New York or Boston, heading to their vacation homes on the Vineyard or Nantucket.

Bobby was the owner and day cook. He was a large mustachioed man with large Rodney Dangerfield eyes. He was quite entertaining, sometimes flipping pancakes behind his back onto the plates as he mangled lyrics, singing along with the radio. Once he emerged from the walk-in cooler yelling, “Brucie! They’re all over me!” He had about six lobsters hanging by their claws on his apron, right over his groin.

“Some days chickens, some days feathers,” was another one of his favorite sayings. He would say it after breaking up one of the epic arguments between his wife and his mother, who both worked at the restaurant. They despised each other intensely and argued often, and viciously. Bobby’s dad, Gramps, worked there as well. He would observe these confrontations wordlessly, not daring to get involved. Eventually, when the combatants cleared he would look at me, shake his head and mutter, “Wuh.”

Lulu was a diminutive waitress; a lifer who had worked the summer days for years. “Bobby,” she said one morning as she waved the order ticket in the window, “This gentlemen would like his pancakes well done.” Bobby looked at the ticket and clipped it to the rail along with the others. A few minutes later, the hot cakes were under the heat lamp waiting for delivery along with the rest of the order. Lulu took the order out, and about a minute later reappeared in the window.

“Bobby, he says these aren’t well done. He says he wants his pancakes well done.”

“Well done. Pancakes?” More of a statement than a question.

“Yes. Well done pancakes.”

Without expression, he put the same pancakes back on the grill until they turned a little more brown. Re-plated, Lulu delivered them back to the diner. Less than a minute later Lulu returned to the kitchen, plate of pancakes in hand. She peered over her glasses, “Bobby, he says these are the same pancakes he had before. He wants NEW pancakes, and he wants them well done.”

Bobby looked at me without expression. “Brucie, fire up the broiler.”

Lulu and I watched as Bobby put the pancakes under the broiler flames. He lit a cigarette, rested one hand on the steel broiler handle, and leaned against the refrigerator. The three pancakes started to smoke slightly as the tops blackened. He turned them once, leaving slight parallel sear marks from the grill on them, like you see on restaurant steaks. He put them back on the plate and wordlessly handed them to Lulu. The looked more like hockey pucks than pancakes.

“Bobby, I can’t take these to him.”

“Just give them to him.”

“Bobby…”

“Just give them to him.”

Thirty seconds later we observed a rather hostile looking gentleman approaching the kitchen, plate in hand. Bobby put down his cigarette and grabbed a large wooden-handled stainless steel spatula. It was a heavy commercial model, manufactured by the Russell Corporation. The man came through the swinging door. He had enough time to say, “Just what in the …” before the flat metal side of the blade came down between his eyes, right in the middle of his forehead. The pancakes flew into the air and the plate came crashing to the floor. As the man fell backwards, Bobby grabbed him by the shirt and dragged him up the steps, throwing him onto Water Street.

Lulu and I stood, slack-jawed. Bobby descended back into the kitchen and lit another cigarette, as if nothing had happened.

“Brucie, looks like the rush is all over. Better get back to those dishes.” I walked back to the dishwasher, and through the steam watched him sweep up the pieces of broken plate.

I worked there for three summers, eventually as short-order cook. Six days a week, eight and a half hours a day, starting at six thirty a.m., at a starting salary of 100 dollars a week. I loved almost every minute of it.